|

The first time I ever created a vision board was during my GCSE English Literature class. We were dissecting articles, and trying to decide the mood that the writer was trying to achieve. I am a very visual person, and so I love a vision board for my own life, be it a Pinterest board for what I want to wear or eat, or a collage slipped into my journal to keep me on track with my goals and aspirations. But to date I have never created one for a manuscript.

Yesterday, I finished what can be loosely defined as a first draft of my next book. It’s rough and ugly, and wildly inconsistent, but the skeleton of a story is there. Any written work today would have been pointless, though. Because before I sink back into it, I need to decide upon a few important things before I undertake the first major edit.

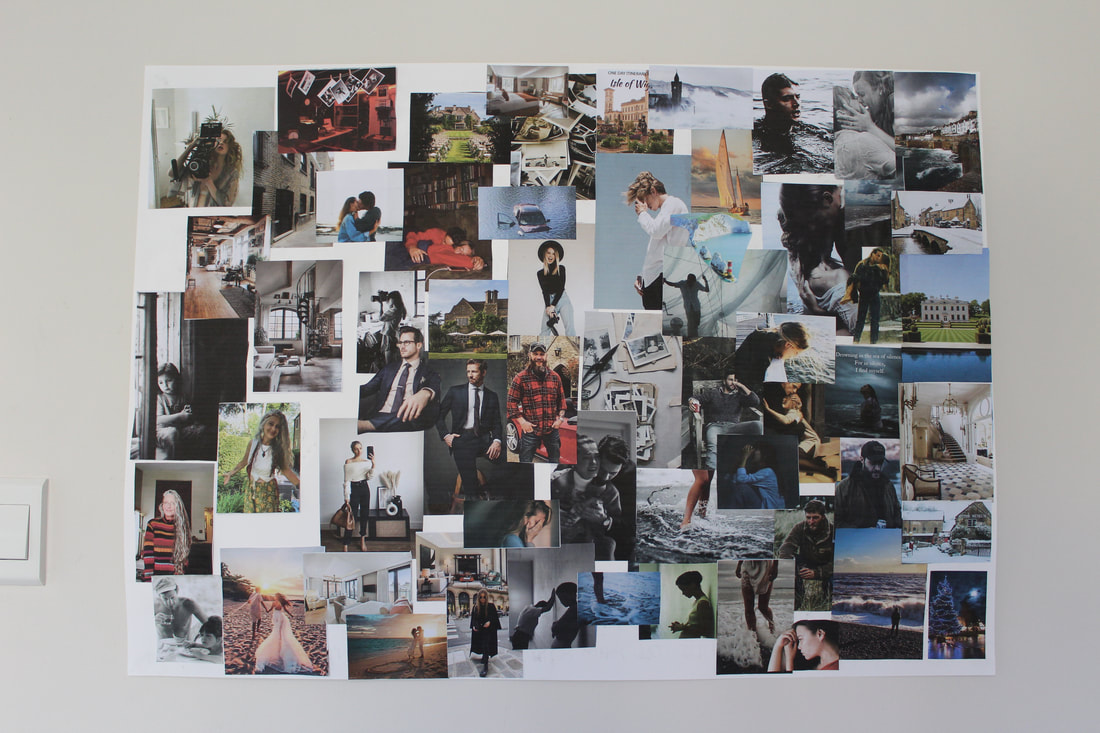

And I have found today that creating a vision board helps me answer these questions. I found images that relate to important parts of the story, or important characters and their interests, and printed them all out. Then, I began to cut and categorise. I kept the images for one character together, and then try to put each group into a rough sort of timeline. This created a sort of storyboard of emotions and events. I began to understand the mood, the setting, the colours. Weather patterns as the story unfold became clearer, as did the things that stir the senses, like smells, texture, and taste. I didn’t understand the importance of water in this manuscript, or the part buildings were playing until today. Now that has become clear. When I look at the board I can see the arc of my characters lives, and the points where they intercept. To anybody else, it might just look like a collection of images, but to me the story is told visually, and I know the temperature and nature of the story. I can see the highs and lows and how my characters feel at each moment in the story. Even their reasoning, the thing that drives them to behave the way they do, is clearer to me after this. I have long been aware of the positive effects of creating a vision board. But now I see it can also be so helpful when it comes to writing. So, now this board will stay on my wall through the edit, and I will refer and add to it as and when I need to. Instead of panicking about this next step, which honestly, was feeling a little overwhelming, it's easier to see where I'm heading, because the map is right there in front of me.

0 Comments

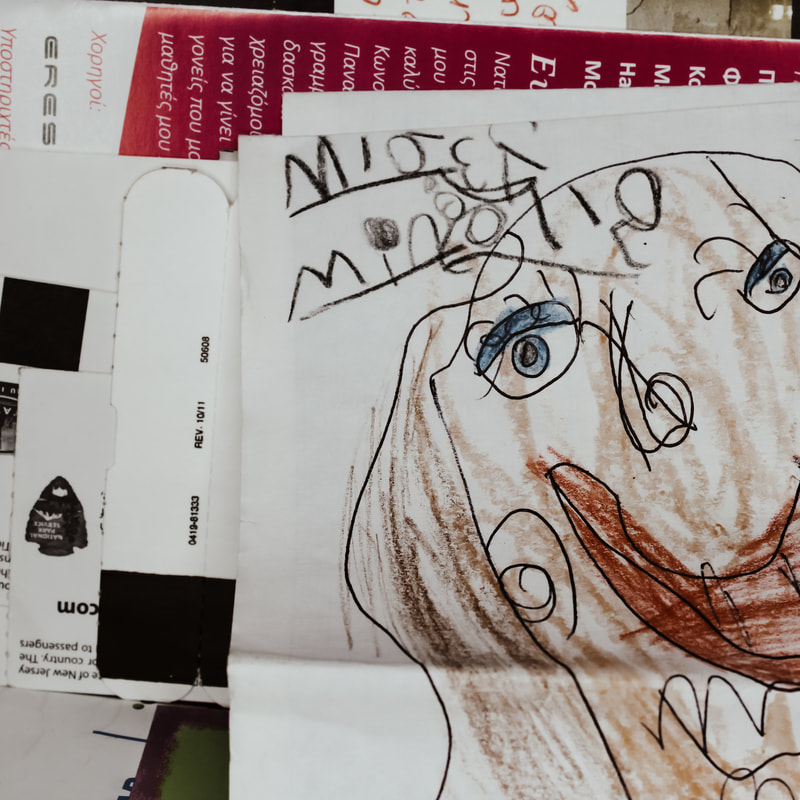

23/1/2023 Should I give up trying to be a writer? Questions we all ask ourselves at some pointRead NowOver on Tik Tok last week I was talking about how to find an agent as part of a series, Writing Tips for Writers. I could talk to you for hours about this, because the story is long and convoluted. I won’t though, because I managed to scale it down into a one-minute video. The short version goes something like this. I wrote a book, shipped it out to agents, it got rejected. After emigrating I wrote six more, and self-published five. My seventh book was all set to be self-published too, with a title and cover ready to go (which I still think was great) but at the last minute on a hunch/whim, I decided to do a round of agent submissions. That got me representation, a book deal, and rights sold in 17 territories. There were a number of moments during that journey where I thought about giving up. After book one not getting picked up. After some bad reviews of my first book once it was for sale on Amazon. After book five, when I made a half-hearted attempt to get an agent and didn’t. But something kept drawing me back for another go. Considering that it takes the best part of a year for me to write, edit, and produce a book, what is it that kept pushing me to try? Writing, by its very nature, is a practice. It’s something that we are doing from the age we can hold a pencil, finding a medium by which we can express our thoughts. My five-year-old is learning to write at the moment, and writes phonically on her drawings. While she is not a writer by the conventional definition, she is making her first steps onto that path. Because the first time I tried to write a book, it wasn’t all that well executed. It awful, and it didn’t look like a five-year-old had done it, but that was only because I had spent a lifetime reading, and knew roughly what it was supposed to look like. Perhaps in the same way my daughter can draw a face with two eyes, a nose, and a mouth. Creative skills are something we are born with. But the difference between me and my daughter drawing a face, or me and my twenty-year-old self attempting to write a book is practice. Skills are acquired, then refined over time. Writing books that people like, and that stirs their emotions is very rarely something we do right from the first try. And yet, when I wrote the first one, and sent it off in the hope of securing an agent, I really thought it was. It wasn’t, and the rejection hurt. But each book I have written, and therefore each rejection, was a step further in my journey. Each of those books contributed to the writer I am today, and to the success of any book I might write in the future. To date, I have written;

By that total, I am currently writing my fifteenth book. I knew that a couple of these in this list weren’t good enough. A couple of them came at a cost, and it was a hard hit to take. That third thriller that didn’t sell….ouch. But still I continued to write. In fact, that first women’s fiction book, written on the back of a no-sell, went on to be the best deal I have had to date. I wrote for a year after that rejection, believing I could write better, and I did. All of this said, I have no qualifications in literature, save an A level. No connections in publishing. But what I have is a desire to write, a willingness to accept it as a practice, and I was committed to its continued improvement. And finally, of course, persistence. Because persistence, for any writer who is committed to improving, is the single most important factor when it comes to getting a book deal. If you would like more tips and advice on writing, like how to secure an agent, be sure to sign up for my newsletter, where every month I share something that I think will help you. You can sign up here. 13/1/2023 hOW should I SUBMIT my manuscript TO A LITERARY AGENT - top three things to rememberRead NowWhen I first began writing, I had no idea about how hard it might be to get my work in front of readers. Looking back, my naivety kind of makes me roll my eyes. I really thought that if I had written a novel, had finished a whole book, and sent my manuscript to a few select agents, that would be it. I'd have a novel published. I couldn't have been more wrong. There was something I needed to know; how to submit my manuscript to a literary agent. And during my first round of submissions with my debut novel, I didn't. Those first manuscript samples, sent out bound with a lovely red string to help it stand out - my thinking was that it was a medical thriller, you know, blood, red, danger, death - didn't get me very far. In fact, by the end of my not so thorough approach, all I had to show for it was a box of returned chapter samples, and a collection of stock rejection letters, which for a time I kept for prosperity. It was, after all a brush with the publishing industry, and I didn't want to throw that away. Because, what I was fast beginning to realise was that getting a rejection letter was part of going out on submission, and one of the necessary steps I needed to take on the way to getting noticed. It took me another six books after that, and a lot more rejections, before I found the agent who still represents me today. But in the interest of helping you, dear writer/reader, reduce the dreaded R-number, I'm going to tell you what I think were the three most important things that I did that helped me secure an agent. So, number one. I was beyond organised. When I first approached an agent, there was no such thing as an email submission. Now, thankfully, most submission processes, if not all, are done digitally. This makes it in some way much easier (and cheaper), but it is much harder to keep track of where and to whom you sent what. Based on the fact that most agents want the same thing, i.e. a cover letter, a synopsis, and a three chapter sample, it's a good idea to get that prepped ahead of time. But beware, some agents want specific formats (font, font size, line spacing etc) and others might want more words and less synopsis, or vice versa. Agents are very clear about their requirements, and fortunately they all have a website with this information easily available. Use it. And follow it to the letter. Once you have your submission pack ready, keep track on everything you do. I used Excel. I recorded when I was sending, how long they told me to expect to wait, and included separate columns for potential responses. And most importantly, I knew when I was supposed to send a reminder. My agent received my manuscript two months before I contacted her again, letting her know I had received a full manuscript request elsewhere. That email made all the difference. Three days later I had representation, plus one other offer. Without the nudge, it might never have made it past the slush pile. Next one. Professionalism An agent is not a hobbyist, and so when they offer you representation, they want to know they are working with somebody who is professional. You only have one way of showing them this in the first instance, and that's the cover letter. So, you'll want to make sure that yours in in tip top shape. It should be concise, include the information they ask for, and have everything they need to know about you and the manuscript. Consider that you are applying for a job. A little note about comparisons. It's the hardest bit, or at least I think so. Offering comparisons for your work shows that you understand the market. But don't just choose the obvious ones. How many psych thrillers do you think we're compared to Gone Girl in 2015? A lot. Choose something that other people might not think about, and if you can offer a few, or it's a cross between this and that, or a this meets that, then it really helps set the scene for their reading. So follow their website submission instructions, and make your cover letter professional. If you do speak to them on the phone, be polite. Over email, be timely in your responses, so that they will understand that you are easy to work with. Make yourself a great prospect for them, and if you've written a great book, they'll be just as keen to work with you as you are with them. Finally. It's a big one. Persistence The hardest one of all. After my first effort, I decided against another submission for a while. I'll be honest, being rejected, and realising my own level of naivety hurt my pride. I gave it one half hearted shot around book five, and when that didn't go well either, I considered never trying again. It was only after a chance conversation with somebody who approached me looking for advice about finding an agent, that I wondered whether I should give it another go. I decided that I would, and also that it would be my last effort. And so I made it a good one. It was only in doing this that I realised how lame my previous efforts had been. And so I revised that new manuscript until I could recite parts of it in my sleep. I researched agents, and who represented which writers. I listed all those I'd like to apply to. I made a schedule, saved my files with the right name, and agonised over the cover letter because it felt like something that could induce immediate failure. In short, I became obsessed. I'd like to tell you now that I went over the top, but I don't think that's true. The competition is high. You need to stand out, perhaps now more than ever. Deals are scarce, and it is harder than it used to be to sell a book to a publisher. I don't say that to put you off, only to inspire you to execute your submission to the very highest standard you can. And if you do that, when you do receive that first rejection, you'll realise that is just part of the course. I wish I could find my submission tracker to share with you. I think it is saved on another computer, and I will look for it this weekend. But I do remember that it was over 100 submissions long. Nearly all of those were rejections. But just remember this. You don't need over one hundred agents to get published. You only need one. If you would like more tips and advice on writing, like how to secure an agent, be sure to sign up for my newsletter, where every month I share something that I think will help you. You can sign up here. I didn’t grow up in a city as such, but it was definitely something like town-based suburbia. There wasn’t much in the way of nature on our doorstep. But as a teenager, a kid even, I had a thing about getting outside into something that felt like an escape. In my town there was a particular road I liked to ride my bike along. It wasn’t much, a lane that lead away from an industrial area, that on one side was nothing but hedgerows. Berries grew in it, and if I looked down I could imagine I was somewhere else. There was no curb, no traffic. Just a few lucky houses. One of my most vivid memories as a child was a spring or summer day. I might have been six, maybe seven. A hazy sky that seemed golden as I looked up, alive with bugs and pollen, and in the distance a tree near a river that might have been a willow. Dragonflies landing on Cow Parsley taller than me, and I think, perhaps, a picnic. I asked my brother, and he might remember that day too, although neither of us are sure where or when it was.

Nature, and being in the countryside always felt like a big breath in for me. Anxieties I didn’t know I was carrying would fall away, and I would return to life feeling recharged. Or perhaps more like I had just experienced it. As an adult not long would go by before I was returning to the wild, river walks, or mountains climbs. To weather that wasn’t my friend, but whose company I enjoyed. In moving to Cyprus there was a whole different type of nature to discover. Mountains were much larger, and yet the wildness was lost. Most rivers needed a sign so that you wouldn’t miss them. Fields were not in short supply, yet they were brown, dusty, and the plants looked different. The mud wasn’t dark. So much about the world around us tells us that we are home. In a new country, there is more than new one language to learn. Yet there are places here that I have discovered now, that feel like something I know. Something maybe, that I knew all along. And only this week I have discovered a new escape, a Venetian bridge, hidden in a small valley, accessed via roads that almost nobody would bother to drive down. There was no curb, and when we reached our destination, no route going forward. The road became the river, and to leave we would have to turn around in its flow. In arriving there, we sealed that place off from the rest of the world for a little while, and if anybody else were to try to find it, they would have instead found us, blocking the way. The bridge itself was a beautiful hodgepodge of stones, impressive in its continued perseverance. The top of it was I suspect long overgrown with grass and plants. The river itself which ran over a weir to track beneath, seemed to come from almost nowhere, the source hidden in deep thorny undergrowth. And as it flowed away from us, it carved a route through a rocky terrain, over fallen trees and through rotting roots, to a rockface covered in moss. It was darker as I waded through, following its path, cooler and damp. The earth of the riverbank might have been brown, saturated in ground water, had I have been able to see it for the fallen leaves. Around me all was quiet, nothing but the flow of water over polished rocks and the crunch of my feet through the brown autumnal carpet. I wanted to go on, deeper still, but something called me back. Time restraints, probably. A lunch reservation. The thing we define as life. But for a moment, we stopped. I felt nourished by the time in nature, and took the chance to relax, something I rarely seem to do. We hung back as the kids threw rocks, splashing each other with ice cold water, the knees of their trousers grey with dirt as they tried to build a dam. For a while, nobody worried about time. Even me. We picked flowers, felt the rush of water against our fingers, picked seed heads from trees, then more from those that had fallen to the ground. For two hours without phone signal, we did nothing. We watched. Chatted. Planned a trip. Craved a Starbucks, like we had been lost for hours. Maybe in truth, we had been. But I think, for a little while at least, that was what we wanted. We've all heard the 'new year, new me' mantra. It’s very easy around this time of year to feel the push to make new year’s resolutions. I’ve never really thought that this was something for me, and yet this year I find myself being drawn a little into the idea. A few weeks ago, I picked up a beautiful Filofax, Norfolk it’s called, in tan-brown leather with many blank pages which I am already filling. My brain often feels as if it's on overload, in too many places at once, with too many to-dos and points to remember. The Filofax therefore was brought in as a treatment regimen, an analogue version of my higher self, to cure the disease of forgotten tasks. Like paying bills, let’s say. And yet it also seems to have become an outlet for all my thoughts. It even has a place where I can slot my journal. And perhaps this is the reason why resolutions seem possible this year, rather than pointless. Because, when I am not overloaded, my brain has time to process things like desires. Hopes. Goals. Perhaps because of my Filofax, what I processed by late 2022, was that certain things did need to change.

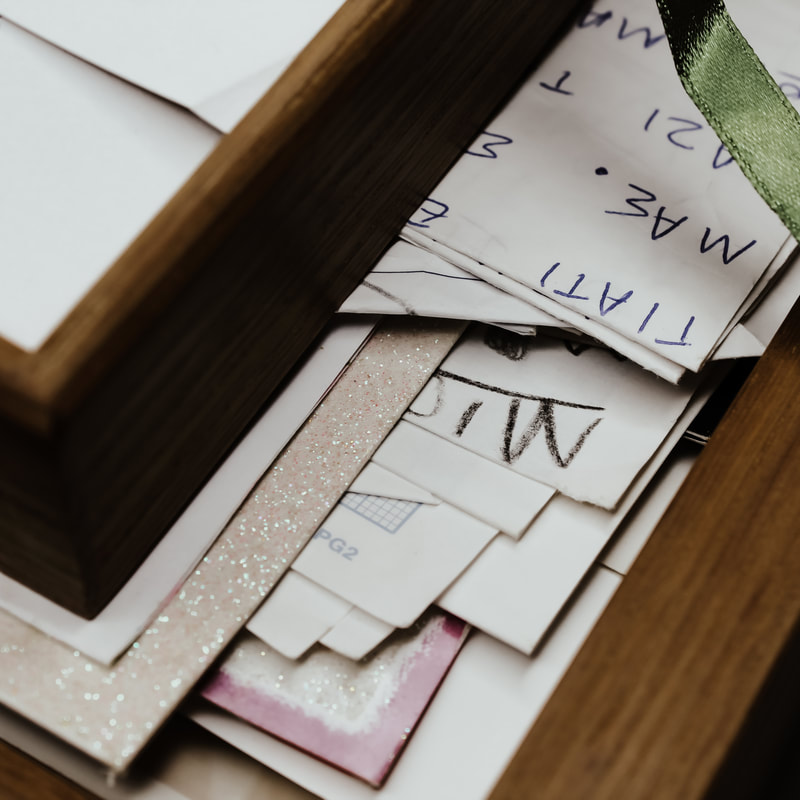

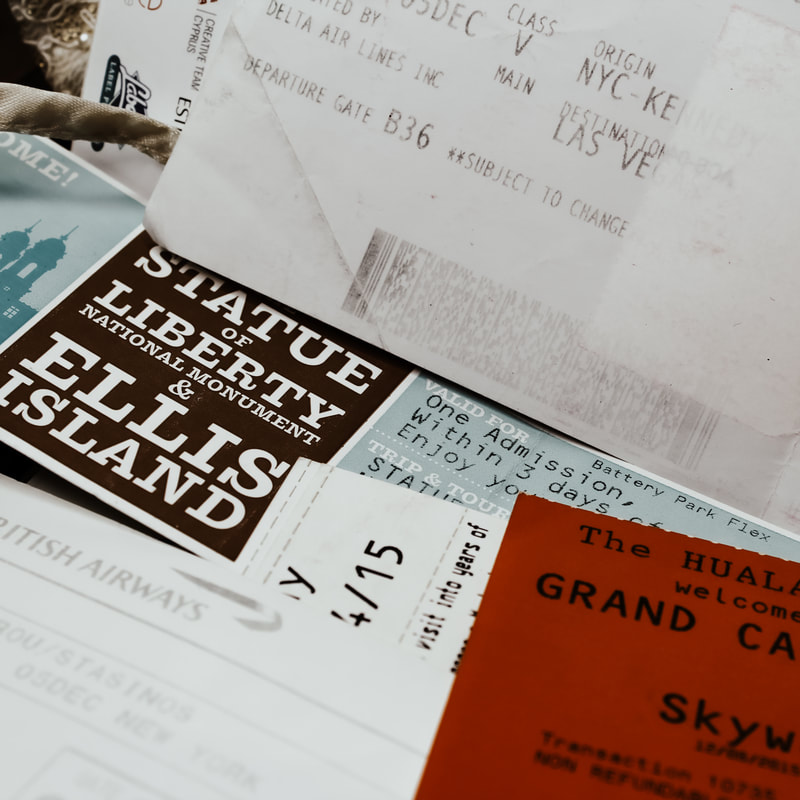

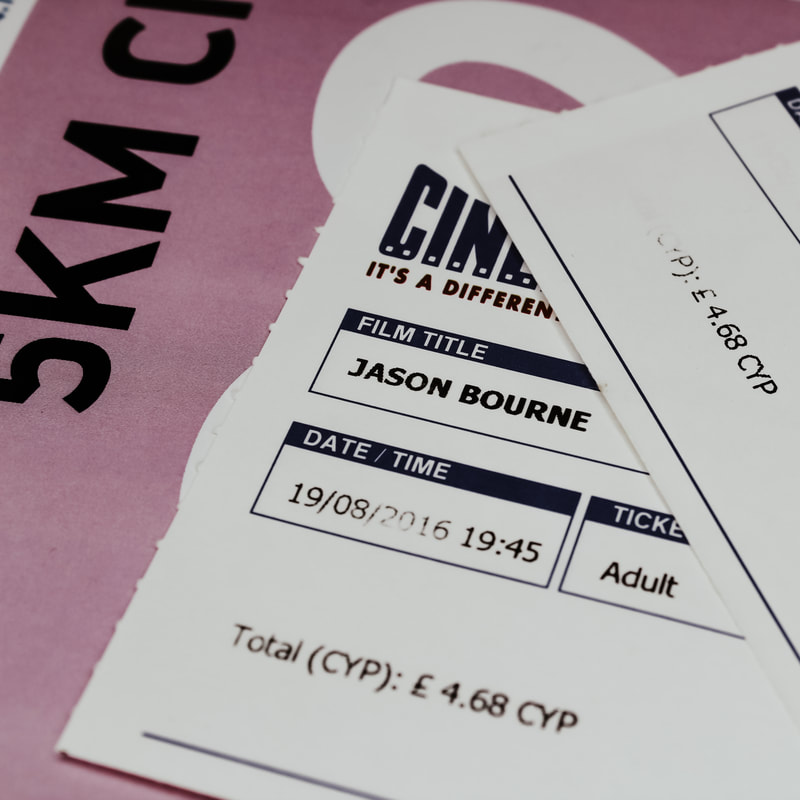

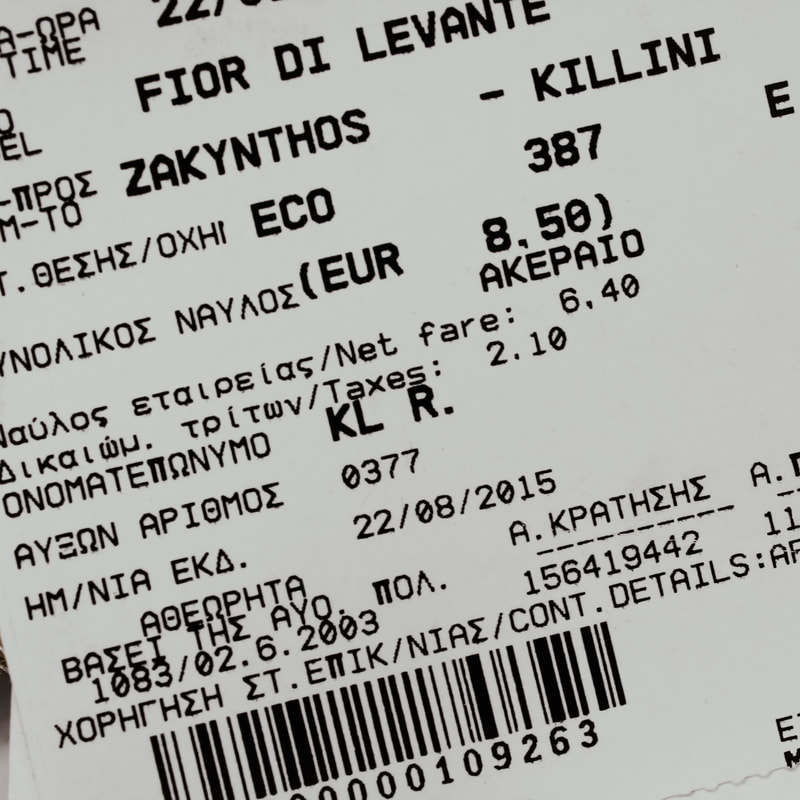

The outgoing year was not one I’ll treasure. Of course, there were wonderful moments. Travel opened up again. I fell in love with Florence and it's history. My daughter’s speech improved immensely. She entered reception and loves it. Personally, I had the utmost pleasure of publishing another book. And yet I feel that by the end of 2022, I had lost some of the clarity about what it was I wanted from my days. And when you don’t know what it is you want, you inevitably end up accepting things you don’t. So, this year, for the first time, with a bit of a lead up in December, the first day of the year became my reset point. I did a lot of looking back, reflecting upon what I want and don’t want. What I like and don’t like. What is it that brings me joy? And I found that besides those around me whom I love, the thing that provides me with the most joy, is creativity. Writing for me, has always been my medium of choice, a way of expressing my thoughts and ideas. My emotions too, the things I fear, love, and cherish all go into my stories in some way or another. There’s a reason why my books are all thematically inclined towards the idea of understanding oneself, of what makes a home, and of where the lines between the past and present are blurred. And this week, during another New Year reset, I found an old wooden box under my staircase. It is stuffed with hundreds of useless items that I thought to store. A pressed coin from the Dali Museum, name cards from weddings, and a ticket for the Metro in Paris. Birthday cards, apology notes, ribbons from places long since forgotten. I recall that I once called it a memory box. I was a magpie, for little things, collected along the way. I no longer do this, namely since Covid, and perhaps also it trailed off when I became a parent and had no space for thoughts of anything but milk and sleep schedules. For a time, I think, I stopped looking outward. Maybe as a result of this I now collect thoughts, all written in my journal. But both methods are I think fulfilling the same function. To create a living document of who I am and where I’m at. Of what I like, and what made me feel loved. My intention is not to remember every single moment, but rather be clear about the things I cherish. It's about being intentional with the life I live, by collecting items and words that connect me to where I’ve been and felt present. And so, it's with this in mind that I make my promises to myself this year. Not a resolution, but an intention to live with my gaze cast out wide instead of inward. To be part of and enjoy the process of life and creativity. To stop perhaps, being an observer, and instead become more of a participant. And to once again pick up a leaf that will one day become nothing more than dust in a forgotten wooden box, and say to myself that in that moment, in that day, I found happiness. 15/11/2022 When is the right time to shelve a project? Taking the difficult decision to stop working on a manuscript.Read NowA couple of weeks ago I shared a hyperlapse video over on my Instagram profile which involved me cleaning up my desk and removing a lot of my sticky notes from the wall. This happens on an infrequent basis, but always for the same reason; it signals the end, be it a full completion or a temporary hiatus, of a work in progress. Now obviously, for reasons of being economical with the amount of wastage in my writing, it’s always better if the end of a project aligns with the completion of page proofs, that magical moment when fresh books are landing on my doorstep. But projects do not always end there. Some have the good grace to arrive as little more than brief ideas, enter and depart with equal speed and efficiency. They remain shallow, and do not linger. Yet others drift in, stay a while, grow to the size of 50, 60, even seventy thousand words before they begin to flag. Grind to a halt. Some projects undoubtedly call for a break, and some never get off the ground in the first place. But how do you know when to stand up and wave the white flag of surrender on an unfinished novel?

Well, sometimes it’s really easy. Simply, your agent tells you it’s time. And in this instance, for me, the end of my current project has come in much that way. There is still merit and value in the fundamentals of the idea, but the overall structure and execution does need a moment for consideration before any valuable conclusions can be drawn about the best way forward. But what if there is no external source telling you to stop? How do you know when to call time? Shelving any number of thousands of words feels awful, and should never be a decision taken on a whim. It’s hours spent at your desk, and probably many more spent in contemplation and research. It doesn’t even feel good to delete a thousand words from a manuscript during the editing phase at times, so scrapping a whole project, no matter where you are at with it, is bound to hurt. But therein lies the real question; are you really scrapping them? Projects come unstuck for any number of reasons. It might be that you need more research before you push on to finish. It might be that you made a mistake further back in the manuscript and that retracing your steps will bring you to a solution. Perhaps you have inadvertently written across two genres, and the traditional publishing world most likely won't know what to do with it. Taking a break, making a slight change to the plot, structure, or the way you tell the story might be all you need. My last manuscript needed a change in tense, and it elevated the voice of one of my main protagonists, and that made all the difference. Or rather, I think it did. I'll let you know if it sells. But, if you can’t see the way forward, it could be that what you have written simply isn’t working. That in fact, it doesn’t have a future. But that doesn’t mean the process of writing, no matter the length of the current manuscript, has been in vain. For whatever reason you take a break from a project, no matter the level of permanence, the words haven’t gone to waste. Even now, as I shelve 70,000 words, I can see the value in having written them. They are not simply being scrapped. I wrote six books before I established a relationship with my agent, and when I look back now the earliest words were not all that good. But still, they were not wasted. Each was a step forward, and the lost words of discarded manuscripts push us further as writers. They help to hone a craft, and develop a narrative voice. They teach us where our passions lie, and how to filter those into the fiction that we create. Those discarded words might teach us what not to do in the future. While it will never be a simple choice, the decision to shelve a manuscript becomes a little bit easier if you remember that every written word pushes the goal of continued publication. I believe it is those lost, quietly filed away manuscripts that help us take the biggest leap in our writing, even if those words are not destined for the printed page. If you spend any time on Instagram, you have probably come across the term 'romanticize the life' on more than one occasion. I've heard it so many times, that now the very idea of it grates me on such a deep level that even writing the phrase here elicits a low grade fight or flight response. And yet is there anything more romantic than the idea of writing a novel? For most people who embark on it, writing has been a long held dream. Something you have planned to do, and put off, and perhaps even started once or twice to no avail. It's easy to think of famous writers in their favoured spots, isolated sheds at the bottom of the garden, remote cabins buried in the woods. Then there are writer such as Victor Hugo who famously locked away his clothes so that he might finish The Hunchback of Notre Dame. But I promise you that no such place is really necessary, and there is no requirement to put some bizarre practice in place so that you might get your book written. So, while writing is, and should remain, a bit of a romantic idea, what do you really need in order to write your first book? The truth is, not a lot. And certainly not any number of items that cost a lot of money. Here are my top five of things you need in order to get your first manuscript written. TimeOh, how we'd all like a little bit more of that, right? And of all that you need to write a book, perhaps the most important (and elusive) thing of all you should put on your list, is time. Even as a fairly quick writer, to get 1000 words on the page, you need the best part of an hour. And many of us don't have hours of spare time in the day, especially when we are maintaining fulltime jobs elsewhere. When I wrote my first book I was working as a physiologist in the National Health Service. That coupled with weekly on-call duties that sometimes required me to be watching electrocardiograms for the best part of a whole night, I sometimes found myself working in excess of fifty hours a week. Finding the time to dedicate to writing wasn't simple. So, I began with using what I had. I found that I could spare an hour each evening, straight after the washing up, and so I used that. And putting that time aside for writing had a cumulative effect. The less TV I watched, the less I wanted to watch . The more I gave to the book, the more I wanted to give. Some of you are probably thinking, well that's great Michelle, but I don't have an hour. Okay, what about 15 minutes? Most people can find that, I think. And if you can write 250 words each day, by the end of the first week you'd have 1500 words, even after scheduling in a day off. Twelve months at that rate will give you 78,000 words by the end of the year. With fifteen minutes a day, you could go from a lofty dream, to a fully formed first draft. RoutineThis point really rides the coattails of my first point, but I think it's worth a place on the list all of its own merit. You need a routine. Let's say you have only fifteen minutes. If you don't make those fifteen minutes a priority, then they will get lost to any number of other things that demand your attention. Even now, as a full time writer, a person who is home alone every day, I have to tell myself to stick to the routine of being at my desk. It's so easy to get distracted by family/household chores/TV/responsibilities in any other area of life you can think of. You have to protect your writing time, and the best way of doing that is by making it a routine. Many experts talk about habit formation as being easier if you can 1) maintain it for a period of time, and 2) stack a new habit onto the back of something else. If you do manage to maintain a routine for a period of time, it does get easier, but I have found the best way of maintaining that routine in the first place is to make it dependent on something I already do. So now, as soon as I make my second cup of tea in the morning, I head to my desk. There's a long list of things that need doing before that, like dog walking, school run, etc etc, but I know as soon as I complete them and make that second drink, I am at work. Just like having a start time for the office. If you are using a smaller window of time, maybe you arrange it so it piggybacks something else, like straight after putting the kids to bed. Maybe it comes once you make your first coffee before everybody else is awake. I don't know what works for you. But if you can make writing dependent on something you have no choice but to do, i.e, when I finish X, I sit down to write, it stands a lot more chance of happening. EquipmentWho knew there were so many essential things to work as a writer. A standing desk, a pomodoro timer, a mechanical keyboard, and whatever else you come across on social media. I have either bought or considered all of these and many more at one point or another. There are so many things you can buy, or subscribe too, but you need very little of it to actually write. The only thing you really need in terms of equipment is a method of recording what you write. For most people, this will be a PC or laptop, and some writing software. For others, it could be a pen and a notepad. You could use a phone. It doesn't matter how the words are recorded, only that they are. A dedicated spacePerhaps this is a bit of a luxury, but I include it because I think it helps. Knowing when you are going to write is one thing, but where is just as important. A place that you associate with writing, and that reduces barriers to doing it. If you have a desk you can use, laptop already there and ready to go, that's great. Just as good is a kitchen counter, or a dining room table. If you can leave out your notes or laptop, even better still. But a spot where you will not be disturbed or pulled away is ideal. Dan Brown wrote the entire outline for his international bestseller The DaVinci Code in his parent's storeroom. I think I read that his laptop was balanced either on a couple of crates or the ironing board. Hardly what you'd call luxurious. But it was his space, and his habit to go there meant he knew when he was working. Maybe your place is your spot on the train, the loo while your kids are in the bath. The car while you wait between appointments. Just know that your space needs to tell you one thing; when you are here, you are writing. SupportWhen I first announced that I was going to write a book, I was lucky that the people in my life didn't try to dissuade me. I was supported, and encouraged. But that won't be the case for everybody. But if you are somebody who does not have the support of your immediate family or friends, that doesn't mean you shouldn't go ahead and make a start. But what it does mean is that you should seek the support you will need elsewhere. If the people in your life can't find their inner cheerleader, find others who will be that for you. A writing group, either local or online, where you can join a community of other writers will do wonders for your inspiration and commitment. Follow other writers and interact with them via social media. The writing community is by its very nature a very supportive place. You will find friends who will cheer you on, even if the people closer to home do not.

There are other things you might find essential as you move through the process. Personally, silence is essential, and I have at times found voice to text software an invaluable way of getting through a period of carpel tunnel. But these five things will get you going. Next time, I'm going to list my top five things that a new writer does not need. Until then, happy writing... In the last post I discussed the issue of quality, and the fact that I don't consider it as all that important when drafting a story for the first time. And so here I thought to highlight that point, it might be fun to take a look at the first draft of some of my work, and compare it with the final edition. Below, you will find the first paragraphs from an early edition of Little Wishes, which at the time was called The Light From Wolf Rock. In fact, this isn't the opening chapter, because that changed in its entirety. An early draft with peppered with letters from one character to the next, and they were all but removed from the final draft. In it's place I wrote a new present day narrative, which changed things dramatically. But this once opening chapter remained as chapter two. Reading it now, I can see that the elements I wanted to get in their do exist, but there is much less finesse, the language is more roughly hewn together, and there is a depth to the internal monologue of the character that is missing. All of that comes over the course of getting to know the characters, and developing the story. I could have worked on this opening chapter for weeks, and it could have been glorious, but I still think I'd have ended up changing it once I'd written the whole book. I hope seeing the way that my first draft has changed will be helpful to you in creating your own first draft of whatever novel you are currently writing. first draft of the light from wolf rockThe first Elizabeth knew of the accident was when she woke to the dull thudding of her father’s boots on the stairs. She sat up in bed, her curtains still open. The sky was dark, broken by a single glimmer of light as it fussed at the edge of a break in the clouds. Summer was over and the onset of autumn had delivered with it the promise of a difficult winter, the kind where the salt spray would infiltrate everything, a permanent slick of saline on your lip. Moments later she heard a door slam, and then from the distance, travelling on the wind, the faintest ringing of a bell. It chimed, frenetic and hurried. Was that a voice she could hear, calling out? She pushed the covers aside and moved to the window, her feet cold on the wooden floor. She saw her father rushing down the street, his boots untied, his pyjamas sneaking out from underneath the tails of his coat. Where was he going at this hour, dressed in his nightclothes? Elizabeth’s father was the village doctor and liked to keep a standard. It was important, he thought, for his patients to see him as organized and dependable, so that they might trust him with their ailments. It helped, he said, with gleaning an honest history. But his absence meant that her mother would be worried on her own. She didn’t cope well with change anymore. Only a year ago she was full of surprises; returning home with little gifts like a new set of paints, ribbon for plaiting hair, or perhaps something as simple as a particularly beautiful leaf which she had retrieved from the ground. Her mother hated the thought of beauty going unnoticed, something of worth being forgotten. That was perhaps the cruelest irony since she herself only last week had forgotten Elizabeth’s name. Elizabeth pushed her feet into her slippers and opened her bedroom door. The landing was long, broken by steps in the middle. It ran all the way from Elizabeth’s room to a door at the other end. The door to her parents’ bedroom was ajar, the light creating a golden shard in an otherwise tenebrous house. ‘Mum,’ called Elizabeth, but there came no answer. Elizabeth picked up the pace, feeling that something wasn’t right. She arrived alongside the landing window, hearing the scuffle of more hurried feet rushing along the winding street in the direction of the sea. A light rain misted against the window, the black road silver in the moonlight where water collected in the uneven surface. Who were those men, and to where were they running? She followed their movement; light shone from the harbor, and something didn’t feel right. FInal edition of little wishesThe first Elizabeth knew of the accident was when she woke to the dull thudding of her father’s boots on the stairs. The dark sky was broken by the glimmer of moonlight as it fussed at the edge of a break in the clouds. The clock ticked at her side, and she saw that it was a little after 1 a.m. Somewhere in the distance a door slammed, followed by the faintest ringing of a bell. Was that a voice she could hear too, calling out? Pushing the covers aside, she jumped from the bed, moved towards the window. As she peered into the street, she saw her father rushing from their home in the direction of the sea. His shoes were untied, the blue and white stripe of his pyjamas flickering underneath the tails of his coat. There had been calls for such urgent departures in the past, but even in the direst of emergencies he always got dressed. Leaving in his nightclothes was unthinkable.

Elizabeth pushed her feet into her slippers and opened her bedroom door. With her father gone, the responsibility for her mother was left to her. Even at the age of seventeen she knew it wasn’t good for her to wake alone. Ahead, a thin slither of light shone from the door of her parents’ bedroom, left ajar in an otherwise tenebrous house. ‘Mum,’ called Elizabeth as she moved along the landing. They tried to keep her accompanied since the cruelty of the confusion had set in about a year ago, yet still there were unpredictable moments like this when she ended up alone. Early onset Alzheimer’s, her father called it. The name didn’t mean much to Elizabeth, but she hated the disease all the same. Only last month they had found her mother trying to take a boat out, with seemingly little idea about where she was and devastatingly unprepared for what might have lay ahead. Her condition was getting steadily worse, just a little bit every day; her presence in their family like a rock ground down by the constant weight of the tides. 8/11/2022 The most important thing you shold know before embarking on writing your first novel.Read NowLast week on the blog, I was thinking about my writing routines, and the kind of practices I used to have in terms of writing my earliest books. Also, what routines I have now, and in what way they differ to how I started out. And now that it is November, officially the month of NaNoWriMo, it seems sensible to linger a while longer on this. Because while it's okay to talk about writing practices, and how they are changed, an important question goes unanswered; what is required to formulate a writing practice in the first place?

For many people this November will be the first time they embark on a novel writing experience. In the past I have also participated in NaNoWriMo, and it was an excellent way for me to focus my time and efforts on a predefined goal. My third self-published book was written that way. But managing to write 50,000 words within one month does, I think, seem a somewhat daunting process. Even now, the truth is, that if I was asked to write that many words in one month, my first reaction would not be positive. I'd be considering the complexities of navigating a plot, of how to make the relationships between the characters blend effortlessly, and how I might make characters I had not yet met for any length of time feel real. But while all of these concerns go against writing that many words in such a short space of time, the argument against taking that challenge ignores one of the most fundamental tents of what it takes to write a novel. If you are reading this, I'm guessing there is a chance you are considering writing a novel. Perhaps it's not your first, or maybe perhaps it is. It doesn't matter when it comes to this point. Because I suspect that at no matter what stage you are at, whether it be your first book, or your tenth, you share a concern that all writers feel to varying degrees. Even now, as I plan my next book, I am aware of it; will it be any good? But if this is your first novel, I feel there is something important to point out, because there is something you learn after having written a few novels already; the first draft doesn't have to be. Only in the practice of writing do you begin to learn that early drafts have no requirement to be good. Some writers might spend months on writing a first draft, only to delete it and start again once that rough attempt gave them what they needed. Others might keep the early draft and cherry pick the best bits. Of course, there are a few who are able to write an almost clean draft from the outset, but I know for a fact there are also many, many sentences and paragraphs that will be scrapped for the majority of writers working today. Even a novel that has been through several edits by the writer herself, and perhaps the agent too, will go on to receive further scrutiny at the level of the publishing house. My first traditionally published novel My Sister was changed dramatically after getting to the publishers. So if you are setting out to write your first novel, whether it be a 50,000 word bonanza during NaNoWriMo, or a more gentle fifteen to twenty minutes per day while the kids are in the bath and you have the laptop propped on your knees, I offer you this one moment of solidarity from somebody who knows; worry less about what you are writing, and focus only on the fact you are doing it. The quality of the writing matters little at this stage. Just get the story down, and you can work on things like voice, structure, and even plot at a later date. The best bits always show up during the edit anyway. Lately, I’ve been thinking about what I used to be like as a writer when I first started, and the kind of practices I used to enjoy. And in the first instance, I came to an unexpected conclusion; that in some ways, I used to be more committed to my routines, and more capable of using my time wisely. Perhaps I am being a little unfair on myself, because essentially since beginning to work full time as a writer I also became a full-time mum until my daughter went to school, and since then we have all being dealing with lockdowns. There was a short period while my daughter was at nursery when I had full working days, but then she wasn’t sleeping through the night, and there was nothing about that period that I could really call routine. Perhaps I have never actually been a full-time writer until now. And that realisation leaves me with the question as to what kind of routine I actually want to create.

As far back as I can remember, I wanted to be a writer. But while it was a dream of mine, I never thought it would be a reality. When we were at school having career discussions, telling somebody that I wanted to be a novelist never seemed like a ridiculous answer. They were looking for a structure, a plan. Which degree, which university type answers. So, when it came to choosing a career path, I plumped for a safe option. I studied science, and ended up working in cardiology in the NHS. Neither are choices I regret, but while I was working exclusively as a scientist, I never felt fulfilled creatively. There was always something missing, but I wasn’t sure I knew what it was. I think it can be quite hard when you have a creative dream in your heart, to know how, where, and when to express it. My first notes for book ideas were made on sticky post it notes, written while I walked around the hospital pushing an ECG or ultrasound machine. I’d be writing plot ideas and character profiles while I made my way to my next patient, and then keep all the notes in my tunic pocket. I think most of those early ideas were flimsy at best, but they were the first seeds of the career I have today. It was the first time I gave myself the freedom to work towards pursuing the creative aspirations that until then I hadn’t spoken of. Besides the stream of ideas I used to note down during working hours, I had no writing routine as such to speak of. I was probably about 21 or 22 years old when I first tried to write a book, freehand, badly executed, and in its final state no more than a few pages long. I didn’t find it easy to find my voice, or even know what it was I wanted to say. I kept making notes, but the older I got, I knew that if ever I was ever going to try to live into the dream of becoming a writer, I had to try to get past that first awkward chapter. It wasn’t until I took a trip to Poland and visited the concentration camp Auschwitz, that I came up with a story that I thought might have some merit to it. The first draft manuscript came in at something like 70,000 words, and it was a medical thriller about a euthanasia program in a dystopian society. It wasn’t easy to get past the early doubts, but I wrote in in the evenings, during break time at work, and during annual leave until it was finished. It felt like I had climbed a literary Everest when I finally typed The End. One manuscript quickly turned into six. Having relocated to the other side of Europe, finding an agent was a little harder then, and as there was no such thing as a digital submission back in 2011, I set about self-publishing each book I wrote. Each one got a little better then its predecessor, and I found editors and designers to help make my products the best they could be. My routine became all about books. And in Spring 2015 I was ready to publish my seventh title. That book was called First Born, and it was about a woman whose mother dies, and her return to her childhood home alongside her very troubled sister for the funeral. But a chance conversation with another writer who wanted to chat about what it takes to find an agent and/or self-publish, made me second guess my own choices. Despite having enjoyed some success in terms of sales of my early books, I began to wonder why I was no longer looking for an agent. I realised I didn’t really have an answer. So, I held off self-publishing that book, and set about looking for an agent. That book, First Born, eventually went on to secure me the representation of my agent, and it sold in seventeen international territories as My Sister. Every day during that period was dedicated to work. That version of me had hours to do it, was obsessed by the very idea of it. I read every book I could, writing all week long, including the weekends. When it came to getting an agent, or publishing schedule, or tasks I had to do, I had spreadsheets for each, a diary, a plan of attack for every step along the way. I was in charge of everything, and for a control freak like me, that was easy. But was 2015 me more dedicated or capable than who I am today? I don’t think so. I used to think hours spent were proportionate to just how much I wanted to publish my work. Now I see it a little differently. Me in 2015 had more time, for sure. But the same love of the written word burns within me now as it did when I sat down to write my first ideas, and the joy of publishing a new title only grows each time I do it. Perhaps now even more so, because I realise what a privilege it is to have this opportunity. So, while I no longer spend fifteen hours a day at my desk, I think that over the course of the last seven years, I’ve learnt that I no longer need to. Writing isn’t something that happens during specific moments in my day. It isn’t a routine. It’s there in everything I do. And so I think there is no routine that will make me a better writer. Writing perhaps should be considered more like a practice, in the same way that meditation or yoga are. Only a willingness to commit to the act of writing can improve your skill. To be committed to perfecting a story. To developing a writing practice that nurtures creativity and provides an outlet for your ideas. Which now that I come to think about it, is what I’ve been doing all along. I don’t think there is a routine I want per se. The lack of a routine is what has allowed my writing to develop. A routine would suggest always doing the same, and I don’t want to do that. I want to give ideas a chance to grow. So I will practice my writing each day, in the knowledge that from developing my skill, stories will continue to form. This, producing books, is perhaps the only routine I want after all. |

Details

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed